TANGIER — They came at 5 A.M, in the Boukhalef neighborhood in Tangier, pounding at the doors and ordering the residents to come out of their homes.

Donatien, a 35-year-old Cameroon native, who today is sheltered in the south of Morocco, recalls the arrival of several vans with policemen and paramilitary forces that report to the minister of the interior. At the bottom of the apartment building, around 50 men, women, and children were piled into a car and taken to the central police headquarters. They would wait there for more than 12 hours without food or water.

“Then, they handcuffed us and put us in a bus,” Donatien says. “There were 36 of us inside, and there were more than 15 full buses.” After several hours of travel and a growing tension in the vehicle, the migrants received some bread, sardines, and water. “Then, at 4 A.M., they left us on the road.” They were about 900 kilometers south of Tangier.

A Moroccan driving by in a small van took the women and the children to the city; the men walked to the main roundabout of the small Berber city, the location of an interim camp for rejected migrants. It was a month ago, and Donatian is still trying to make sense of it: “Like it was a special day to capture all the blacks,” he says.

Donatien is just one of thousands of Sub-Saharans arrested and forcibly displaced since the summer in Morocco. According to the Antiracist Group for Accompaniment and Defense of Foreigners and Migrants (GADEM in French), at least 7,720 people were targeted between July and September in the Tangier region alone.

Has a red line been crossed?

The NGO listed some 89 cases of expulsions from the country, but also the detentions of migrants by Tangier authorities in deplorable conditions. “The people targeted are all non-Moroccans and black, without distinction of their administrative situation,” emphasizes GADEM.

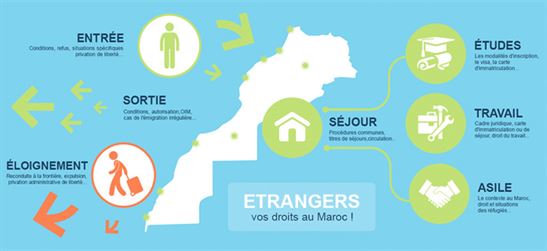

Situated in the northwest corner of Africa, Morocco has often been a transit country for sub-Saharan migrants who dream of making it to Europe. By sea, only 14 kilometers of the strait of Gibraltar separates Morocco from the Spanish coast.

By land, one must cross the borders of the two Spanish enclaves in Africa, Ceuta to the north of Morocco and Melilla in the northeast, ends of the earth surrounded by barbed wire. In the face of this, Moroccan authorities have long oscillated between periods of tolerance and repression, but this latest crackdown in unprecedented. Spain is also considerably affected by the rise in the number of people arriving along its coasts: around 40,000 — mostly Sub-Saharans, but also numerous Moroccans — since the beginning of the year, compared to 28,000 in 2017 and 14,000 in 2016, according to the High Commissioner of the United Nations for Refugees (HCR).

At the beginning of 2017, Moroccan forces had already intensified actions targeting sub-Saharan migrants, aiming to drive them as far away as possible from border zones by forced displacement to other cities of the country: Marrakech, Casablanca, Beni Mellal, Agadir, or Tiznit.

Expulsions and detentions of migrants are becoming more widespread in Morocco — Photo: Dani Salv/VW Pics/ZUMA

This time, a specific event seems to have resulted in Rabat’s hard line: on July 26, a massive assault on the fence at Ceuta resulted in the injury of 15 members of the civil guard. Has a “red line” been crossed? What will happen in relations between Spain and Morocco?

In the small city of Tiznit, on the edge of the Moroccan desert, one cannot sense migrants’ presence except for the drying clothes on the railing of a small, unoccupied house. There are a few mattresses and blankets to sleep, cardboard boxes to shield themselves from the street, and some camping stoves and bowls for meals.

Roland, a 26-year-old Cameroonian, has been here for a month. He was arrested near Tangier as he attempted to take to the sea with 12 other people. They had succeeded in saving 1,000 euros, which they used to buy a small rubber dinghy, some oars, and life jackets. This was not his first attempt. Since his arrival in Morocco in 2012, he hasn’t stopped trying. “I’ve taken almost all the routes: Tangier, Ceuta, Nador… to find a better life, like everyone,” admitted the man who left his home at 19 years old, after a year in law school.

On this day, there are a few dozen new migrants have arrived in Tiznit. The week before, there were between 150 and 200. The authorities leave them in peace and the locals give them handouts. There isn’t an official center to welcome them, just an empty restaurant where they can stay. Lachen Boumahdi, the president of local business Amoudou, notes the welcoming traditions of the region.

“Our city has a long history of emigration. The people here know about it. They were in the same situation in Europe,” he explains.

There’s money to be made.

For the new migrants, the objective is always to continue the journey northward. On the outskirts of the coastal city of Agadir, Donatien, Sam, and Vincent scrape by in a small apartment as they wait to be able to continue their voyage. The three talk of the absurd logic of the closing of the European Union, but also of the limits of the integration politics in Morocco.

Vincent, a husky 37-year-old with tattooed arms, has spent three winter months in the Cassiago Forest, near Ceuta, where groups of migrants hide while waiting for an opportune moment to attempt to cross the barb-wired fences. Injured in the leg while trying to climb a fence, he now only tries by the sea. “Today, it’s the Moroccans who control the business. They realized there’s money to be made. They provide the boat, the motor, the gas.”

Mehdi Alioa, a sociologist and founding member of GADEM, recalls the EU’s strategy since the end of the 90s. “It’s the logic of outsourcing. It’s about turning away those who want to immigrate as much as possible. That’s why we deal with Niger, Sudan, etc. But Morocco doesn’t have to be Europe’s policemen,” he says. “Such politics are disastrous for the image of the kingdom, but also very costly, as the country truly has other needs.”

Since the beginning of the operations of suppression, two young migrants died after falling from the bus that was taking them back to the south. On September 26, a 22-year-old Moroccan was shot by the Navy on a boat that was trying to get to Spain. On October 2, 13 bodies were found after a shipwreck near Nador, in the northeast. Meanwhile, on the winding road from Tangier that leads to the Spanish enclave of Ceuta, the young migrants who were often seen walking along the road have all but disappeared. Hidden in the surrounding forests or in other Moroccan cities, they will eventually return to the North to try their luck again.

https://www.worldcrunch.com/world-affairs/on-the-road-to-europe-morocco-cracks-down-on-migrants#